WTF is a data warehouse?

They say you don't really understand something unless you can explain it to someone who has absolutely no context (see r/explainlikeimfive). Throughout my career, I've struggled to communicate to my parents exactly what it is that I do. For the last 15 years, I've been building analytical database cloud services. My parents, however, don't understand a single word of that; it barely parses as English. How do you explain a database to someone who has never needed one?

"I help people answer questions about their business using data," was the description that I came up with. This, at least, is something they can grok. My dad, who is retired now, ran a small business for 30 years, dealing with suppliers, warehouses (but not data warehouses!), and retailers. My dad needed to get answers to questions about how the business was doing; he could more or less understand that my job was to help people do this on a larger scale.

At MotherDuck, we like to say that one of the things we do differently from other database companies is that we consider it our job to help people solve their end-to-end problem, not just to make their queries run faster. As we like to say, the performance measurement that matters is not how long it takes for a query to run; it is the time between when you have a question and you get an answer. Those are very different things. The job we're doing, then, really is about answers.

In a time when AI is bringing rapid change to many industries and causing people to wonder "just what is my purpose," it is instructive to go back to the beginning and think from first principles about what problem you're solving. What does that look like once AI gets really good at a lot of things that seemed impossible?

The fundamental goal of any data analytics system, the heart of the modern data stack, is what I have been telling my parents all along: answering questions about your data. Allowing anyone to answer questions about their business. Providing you tools that let you get answers about what's going on. It's all about Answers.

Tell me, tell me, tell me the answer

If you were going to propose the ideal interface for allowing anyone to answer questions about their business, what would it look like? Maybe it is easier to say what it wouldn't look like; it wouldn't require them to learn to code. It wouldn't require them to understand dimensional modeling. It wouldn't just spit out rows of numbers.

Even though human language is notoriously vague, imprecise, and ambiguous, we have been communicating complicated ideas for a long time. Imagine instead of telling a computer what to do, you were instructing a person to perform a task. People have some context, generally, and some knowledge about the world. You can ask them to make you a sandwich with peanut butter and jelly, and you don't have to tell them how to grip the jar to open it.

Moreover, since you don't always know what context they have, or you may not always ask in a completely clear way, it is helpful if the person can ask you questions to confirm that their understanding matches your intent.

This works with computers too; if you wanted to ask your computer questions that you wanted answered, you could do it in the same way you would with a human, in the form of a dialogue. You describe in natural language what you want done, the system tries to figure out what you mean and asks you questions when necessary. You might have left out important steps, but the computer should have some context, some knowledge about both the world and about you, specifically. That way it can fill in the gaps. Ideally, the system will be smart enough to learn during the process so it doesn't have to ask you the same questions next time.

What about the output? The results of such a system should represent the answer in whatever format is most effective to convey meaning, probably combining a text explanation with a visualization. Humans are pretty bad at detecting patterns in tables of numbers, but AI is great at building visualizations. Graphs on their own can be misleading, which is why an explanation can be useful. The narrative provided by AI can answer questions that might arise from the visualization. For example, "The dip in usage during the second half of December looks to be because of the holidays. Things recovered in January."

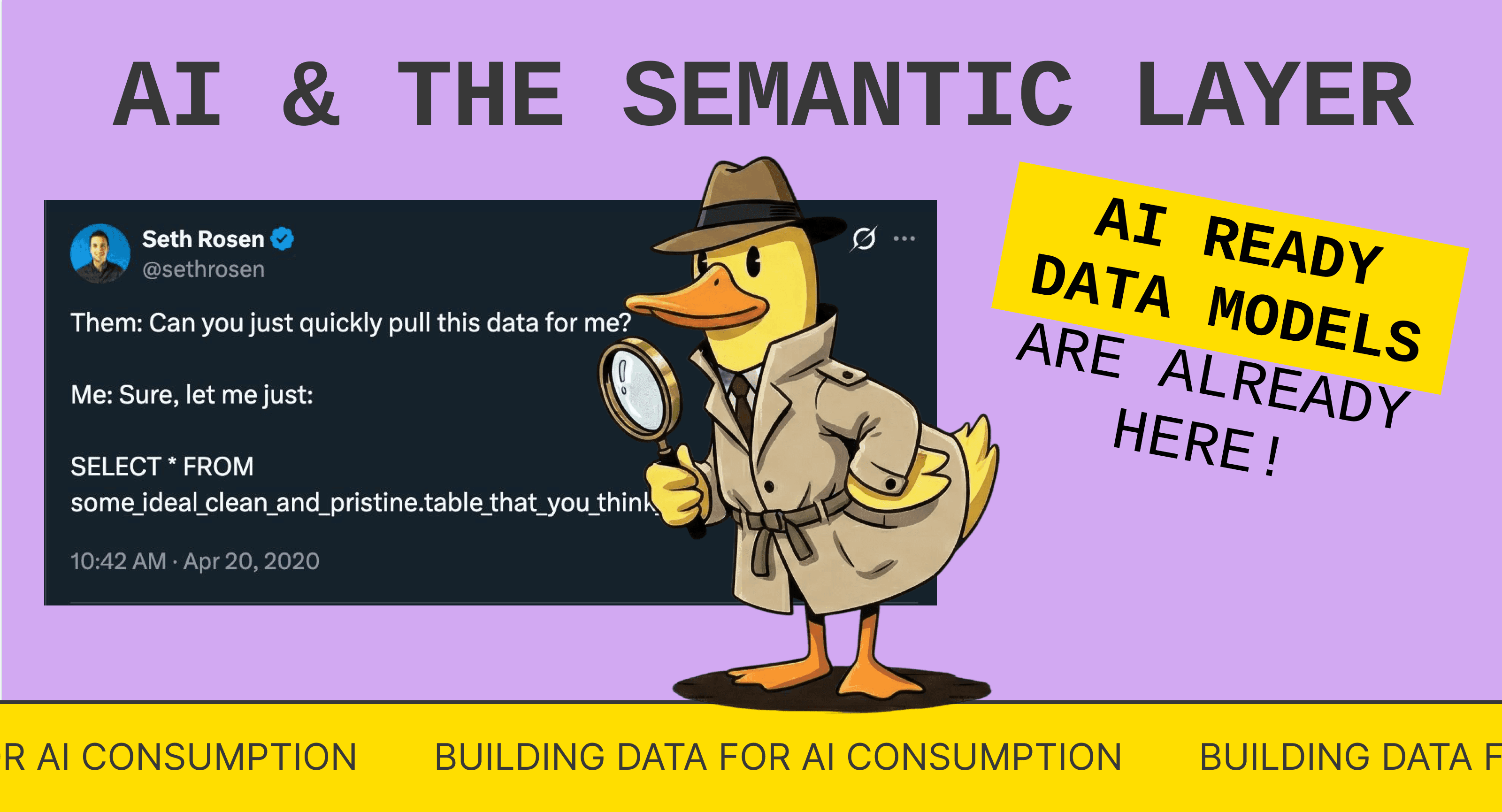

AI ate my data stack

For several years, the "Modern Data Stack" settled into a period of detente; everyone had their swimlane and didn't compete with anyone outside their lane. You had ingestion tools, transformation tools, query engines, and business intelligence, and it seemed like the natural order of things. That has been changing pretty quickly. Snowflake has been eyeing the transformation space like a hungry crocodile. Databricks just announced a BI tool (with AI!). Fivetran, after gobbling up sqlmesh, is merging with dbt. In 2025, agglomeration might have seemed to be the big story, but we're about to undergo a much bigger disruption.

Only a few months ago, it was popular to say that AI was never going to be good at data. I was in the camp that said there was too much in an analyst's head for an LLM to be able to infer it. We're seeing that this was a faulty argument; an LLM can mimic the process of an analyst; they can read docs, probe the data model, and keep running queries until the answers look right. If a human can figure it out, eventually, an AI agent would be able to do the same.

Very Soon Now, with a single AI prompt, you will be able to pull data out of Hubspot, transform it, join it with your data that is in Postgres, answer a question you have, and build a dashboard showing the results. Maybe this will mean that the AI will use Fivetran to pull the data, dbt to transform it, Snowflake to run the query, and Looker to visualize it. But that feels like unnecessary complexity.

To figure out which, if any, of the components of the modern data stack are going to continue to thrive, it is worth asking which ones are the deepest. That is, which tools do you think someone could vibe-code a passable version of in an afternoon, and which would be a lot harder? I'll leave the answer to that question as an exercise for the reader, but at the very least it is going to be an uncomfortably exciting year ahead of us.

The future is already here

It may sound like I'm jumping ahead sixteen steps, when we haven't demonstrated yet that AI is even going to be able to make natural language analytics work. If you look carefully at what already exists, that ship has already sailed. While there are still some quirks, natural language queries work now on real-world non-trivial data. I'd like to share some stories that will hopefully provide an "existence proof" that this stuff is real and works on real workloads.

In December, we launched the MotherDuck Remote MCP Server. We called it our "answering machine" because it, well, is a machine that answers questions. MCP sounds awfully technical and like it is underselling the capability that it enables. I should also note that other query engines have similar functionality; I don't think that this is unique, but I do think we have a couple of factors that make ours work especially well.

Three months ago, I was the largest user of MotherDuck at the company. We all use MotherDuck as our own data warehouse. (We like to eat our own Duck Food). I used to write a lot of SQL queries to dig into some aspect of the business or the technology. For example I'd write a query to ask "What is the percentage of our ducklings that are idle?" or "How much is the free tier costing us?" or "What would the impact be of making a change to pricing?" In the last two months, I have stopped writing SQL in favor of just asking Claude+the motherduck MCP server.

One recent example was when we wanted to model some potential changes to pricing to try to understand the impact on different customers. I had blocked off a couple of hours in my afternoon to do the work. As I got started, I thought, "I wonder whether our MCP server could handle this?" I opened the Claude web client, described the pricing change, asked it to analyze the customer impact, and hit go. In about 3 or 4 minutes, it had spit out the list of customers who would be affected the most, as well as the projection in overall revenue change. This meant I got to spend that time working on the strategy, not the query.

While there are still some things that the LLM gets wrong, it is also often better than me at finding answers in our data. Several times it has given me something and I thought, "How the hell did you know that?" I usually ask, politely of course, because you don't want to anger the robots unnecessarily. And very often it has found some nugget somewhere that I hadn't realized was in the data.

For example, I wanted to understand how some of our new capacity contracts were doing. I started poking around and realized we didn't have the data we needed, so I asked one of our engineers if we could pull some information out of our billing tool (Orb). The next morning, I was talking to one of our salespeople, and he mentioned he had wondered the same thing and had already built a live dashboard. Claude had figured out how to get an answer that I thought was impossible.

This highlights another big surprise, which is how easy it has been for non-technical users to be successful with this technology. Internally, the biggest users of our MCP server have been our sales team. While we pride ourselves on having amazing, highly technical salespeople, I don't know that any of them has ever written a SQL query. But once we turned them loose with the MCP server, they were all of a sudden able to get answers they never would have been able to get before.

They asked questions like, "What interesting companies have signed up in the last 24 hours?" "Which customers assigned to me seem like they might need someone to check in with them?" "What is the biggest risk to my business?" These are not simple or easy questions, and they often combine data that we have with other things that the LLM knows about the world.

A lot of people ask, "What about hallucinations? Do you really trust the answers?" If you had asked me six months ago, I would have said, "You absolutely need a human checking the SQL in the loop to make sure that the AI is even asking the right questions before putting trust in the answers." And this would be doubly true if you're giving those answers to a non-technical person who might misconstrue the result, right?

We've started to realize something that should have been obvious all along: line of business users really know their business already. This lets them sniff out something that looks wrong. An analyst who has to do work for the Marketing team, the Finance team, the Ops team, and the Product team might not really be able to spot the difference between an anomaly in the data and a real event. But a marketer who saw one of their campaigns doing something unexpected would be at least able to ask follow-up questions that could tell whether it was real or not.

What about benchmarks? For the last couple of years, we've been looking at text-to-SQL benchmarks, which seem to hit an asymptote, where LLMs still get it wrong about one in five times. This has been used as evidence that text-to-SQL was not really going to work. After all, if you're going to make a decision based on data and you get the wrong answer 20% of the time, that's pretty bad.

So we tried it ourselves, running the benchmark against our MCP server and various LLMs (Claude, Gemini, ChatGPT). When we then looked into the percentage of responses that were "functionally correct," the results shot up to more than 95%. That is, we did better than the human analyst. Again, this is not any magic that MotherDuck is doing, just giving the right context and letting the LLM do its thing.

Diving for data

As soon as we started vibe-coding our analytics, we noticed we could also produce really nice visuals with Claude. We could even ask it to do drill-downs, brush filtering, regression lines, etc, and then "Make it look like Tufte." Or "make it look like paper charts tacked up in a duck watching lodge." [Our general rule is that no ducks should be harmed in order for us to do our analytics.]

Something was missing, however. While we could share Claude-created lovely dashboards, they were static. That is, if on Feb 1, I build a revenue chart, it could never show me anything after Feb 1. In order to get the newer data, I would have to rebuild the visualization. For example, our head of customer success built a leaderboard that showed internal usage of our MCP server. That was awesome, but it was stuck on the day she created it. There was no way to run it the next day and see updated results.

The inability to have the generated dashboards be "live" was a deal-breaker for using AI generated dashboards in our day-to-day. Sure, it was great for one-off questions and ad-hoc analytics, but if we wanted to build a dashboard that we could look at every day, we needed something different. However, LLMs are great at visualization and are going to continue to get better; we didn't want to take that on ourselves. We want to let Claude be Claude, but also to steer it in the direction to solve our problems.

We built "Dives" to allow LLMs to LLM and to enable them to turn the interactive visualizations they create into live results. Dives are data visualizations that you create with Claude, Gemini, or your favorite LLM. (You can even hand-code them and use the API to add them yourself.) Dives contain code to live-query MotherDuck, so when you reload them, they're always up to date. What's more, once you save a dive, it gets published to MotherDuck, so you can use it in the Web UI. You can share them with your colleagues.

What comes after dashboards?

Why didn't we call Dives "Dashboards"? After all, inventing new names for things is generally an anti-pattern. Dives can, however, go beyond dashboards; they can be anything you can code up using an LLM. They can even modify data; they can have forms to fill out. They can look like spreadsheets with custom controls. They can interact with other services. One of our engineers even built a Pokémon-like game as a dive, and another built a visualization with a Lunar New Year theme. It is all just a prompt away.

The first thing that many people ask for when we show them Dives is to be able to embed them. Because we had to do some magic with headers and permissions to get dives to run in an iframe, they can't be embedded immediately. But this is one of our highest priority improvements that we hope to roll out soon. Please stay tuned.

To get the right answers, you have to start with the right questions

The most fascinating thing to me so far is watching how non-technical users use the technology (we call them NTDs, or non-technical ducks) and how that differs from people who are more used to working with databases and BI tools. Those of us with a more technical background tend to ask questions like, "What was my NRR?" Those with a less-technical bent tend to ask a lot more interesting questions: "What customers should I talk to?" "Is my business growing?" "What are my biggest opportunities and risks?" "What the hell happened?"

In order to best use the technology, people like me are going to need to retrain, step back and start asking the questions we really care about. Every startup founder wants to know (even if they consider it a vanity metric), "What would my valuation be if I wanted to fundraise right now?" Other important ones might be: "Can I afford to hire more people?" "Which of my costs seem out of proportion to industry norms?"

It is thrilling, and terrifying, to be in the middle of such a swift technological change that such questions become possible to answer just by asking them. What answers are you looking for?